Norwood Procedure: What It Is and Why It Matters

When dealing with Norwood procedure, a staged open‑heart surgery that repairs a newborn's underdeveloped heart. Also known as the Norwood operation, it is the first step in treating hypoplastic left heart syndrome and similar congenital heart defects. This surgery reshapes the heart, connects the main artery to the body, and sets the stage for later procedures that will eventually give the child a functional circulation. Below you’ll see how it links to other high‑risk surgeries and what patients and families should expect.

How the Norwood Procedure Relates to Open‑Heart Surgery

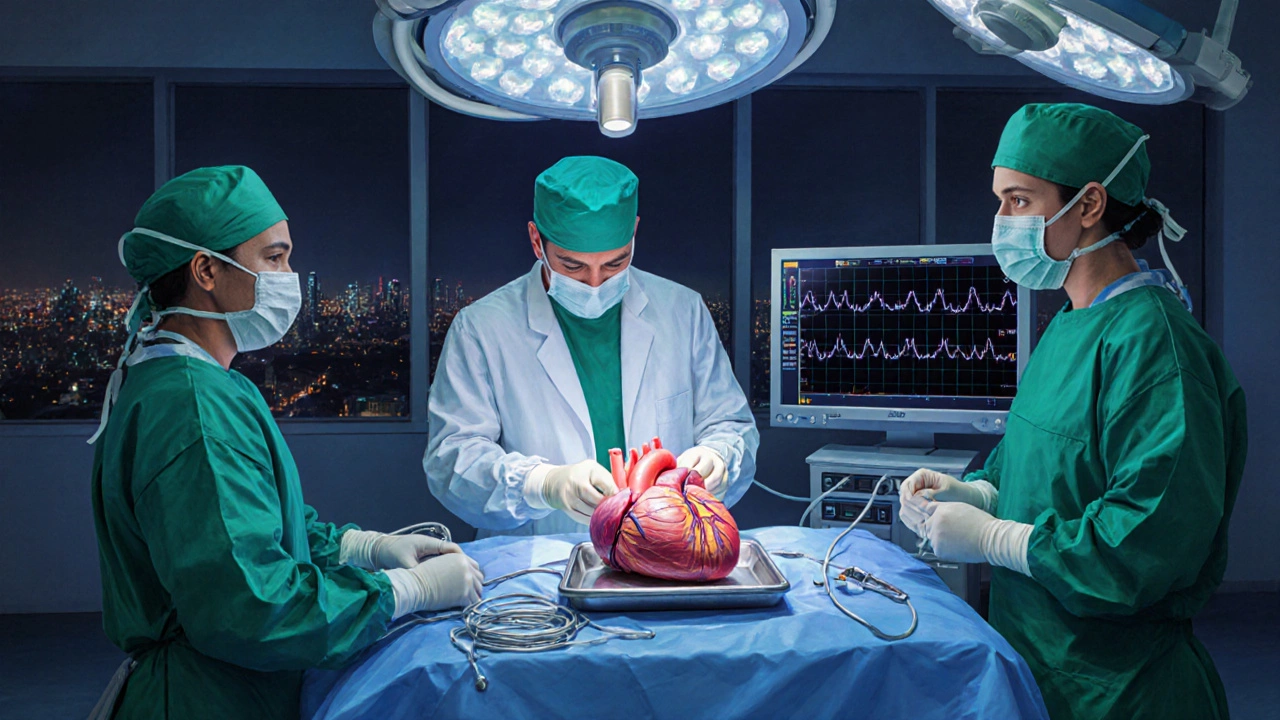

The open‑heart surgery, any operation that requires the chest to be opened and the heart temporarily stopped is the technical backbone of the Norwood procedure. During the operation, surgeons use a heart‑lung bypass machine to keep blood flowing while they reconstruct the heart’s vessels. Because the infant’s circulatory system is tiny and fragile, the procedure demands precise timing and meticulous suturing—mistakes can trigger serious complications like bleeding or low oxygen levels. The risk profile mirrors other major cardiac surgeries, making pre‑operative assessments and intra‑operative monitoring crucial. Understanding these shared challenges helps families compare the Norwood operation with other complex surgeries they might encounter later.

In addition, the Norwood stage sets expectations for congenital heart defect, a structural problem present at birth that affects the heart’s ability to pump blood. Babies with hypoplastic left heart syndrome essentially lack a functional left ventricle, so the Norwood procedure creates a new pathway for blood to reach the body. This connection is temporary; later stages—the Glenn and Fontan procedures—complete the repair. Knowing the underlying defect clarifies why the Norwood operation is only the first step and why long‑term follow‑up is essential.

After the chest is closed, the journey doesn’t end. post‑operative care, the period of monitoring, medication, and therapy after heart surgery becomes the next big hurdle. Infants often stay in the intensive care unit for weeks, receiving ventilation support, medications to manage heart pressure, and careful fluid balance. Parents are taught how to spot signs of low cardiac output, infection, or breathing difficulties. The recovery timeline is long, and many families need home nursing support once they leave the hospital. These care steps echo the recovery patterns seen after other major surgeries, such as the “worst surgeries to recover from” list, highlighting the universal need for structured after‑care.

Finally, it’s worth noting that medical tourism, traveling abroad to receive medical treatment, often for cost or expertise reasons is increasingly influencing where families seek the Norwood procedure. Some countries have specialized pediatric cardiac centers that attract international patients with lower fees and experienced teams. While medical tourism can improve access, it also adds layers of logistical planning—visa arrangements, post‑operative follow‑up across borders, and insurance coverage questions. Understanding these factors helps families weigh the pros and cons of traveling for such a delicate operation.

All these pieces—surgical technique, underlying defect, recovery care, and even travel considerations—create a comprehensive picture of the Norwood procedure. Below you’ll find articles that dive deeper into each of these areas, from managing open‑heart surgery risks to navigating post‑operative care and evaluating medical tourism options. Use this overview as a roadmap to explore the detailed content that follows.

Hardest Heart Surgery in Cardiology - Why It’s So Challenging

Explore why heart transplantation, the Norwood procedure, and LVAD implantation rank as the hardest heart surgeries, their challenges, risks, and outcomes.